- Published on

- Wed Jul 9, 2025

Building a WeeWar Map Extractor - Lessons from The Vibe Coding Trap

WeeWar is a turn-based strategy game with hexagonal tile maps. Each map consists of different terrain types (grass, water, mountains, etc.) arranged in a hex grid. I have been a huge fan of this game since its early days - going as far as to build a simple but sadly incomplete Flash (yep) based version of it. But I gave up because having to recreate assets was not my fun time activity.

But have you ever tried to reverse-engineer a game map from a single image? Sure it is not everyone’s fantasy problem

that would keep you up at night. But everybody’s gotta have their weakness. This is what happened when I decided to

extract WeeWar map layouts from their screenshot images.

Deceptively Simple Problem ¶

While one of my (Claude) sessions was doing its thing on a terminal, this game again came up on my mind and I thought well instead of rebuilding the game why not take up the boring activity I had eschewed all those years ago? The challenge seemed straightforward: given only a preview image of a map, extract the individual hex tiles and determine their positions automatically.

How hard could it be? Famous last words.

The requirements were seemingly simple but technically demanding:

- Work with any scale of image (the system shouldn’t depend on hardcoded tile sizes)

- Detect the hex grid structure from visual boundaries

- Extract individual tiles without neighbor contamination

- Handle the tiles typically found in a XxY WeeWar map (large maps could have over 30 rows and/or columns)

This is the “AI Era”. So my first instinct was to throw this to Claude (cli). Here was my first attempt:

You have the images of tiles/terrain in the folder ./AllTiles . Each tile is numbered so the images will be called <tileType>.png and represents a particular kind of terrain (eg grass, sea, dessert etc). Some tiles will have color variations (denoting which player has occupied the tile - eg a building belonging to player 3).

Select the image "./map.png". It contains hexagonal tiles with each tile mapping to one of the tiles in the ./AllTiles folder. I want you to extract each of the tiles the image and save it as R_C_T_P.png where R is the row number, C is the column and T is the tileType and P is which player has occupied the tile. If the tile is a neutral color then you can set P=x (to denote a neutral terrain).

Here’s the test map btw:

So at this point LLMs are smart enough to know they cant tackle it all so it proposed to create a script to do just that:

⏺ I'll help you extract individual tiles from the map image and save them with the specified naming convention. Let me start by examining the structure and creating a plan.

⏺ Update Todos

⎿ ☐ Examine the map.png image to understand the hexagonal tile layout

☐ List all tile types in the AllTiles folder to understand available terrain types

☐ Create a Python script to extract hexagonal tiles from the map image

☐ Implement tile type identification by comparing extracted tiles to reference tiles

☐ Implement player identification based on color variations

☐ Save extracted tiles with R_C_T_P.png naming convention

Now whether at this point whether you thought Claude was going to crush or that it was going to spectacularly fail you both would be forgiven. LLMs are at this crazy place right now but it is best not to always succumb to the Vibe Coding (VC) hype despite what the VCs tell you! And of course I had an alternative flow for this blog regardless of how the LLM fared!

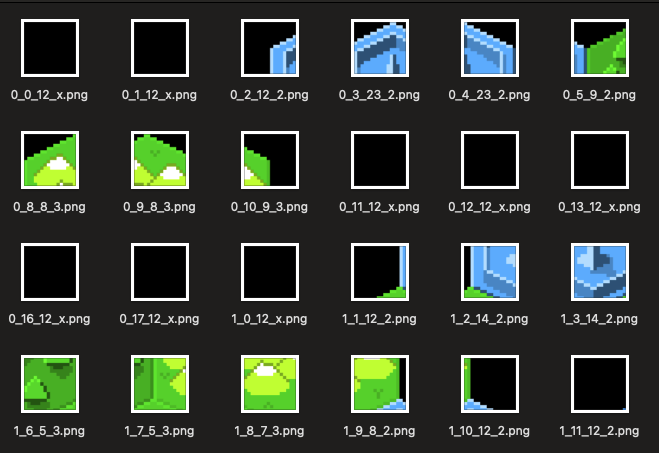

Ok so when I ran the python script it confidently gave me a bunch of images. I was really rooting for it. But examining it files looked like this. Not really off to a great start (i guess it did produce a great looking script that actually ran without errors):

Now you cant just give up on LLMs on the first try. I tried one more thing:

> Ok that did not quite work. You seem to have segemented the image in rectangular blocks instead of along the hexagonal tile boundaries.

Which resulted in hex_tile_extractor.py …

… Which was not actually bad. We now saw the following grid summary:

...

...

...

Row 5, Col 1: Tile 8 (confidence: 1.0000)

Row 5, Col 2: Tile 8 (confidence: 1.0000)

Row 5, Col 3: Tile 4 (confidence: 0.5157)

Row 5, Col 4: Tile 5 (confidence: 0.2023)

Row 5, Col 5: Tile 5 (confidence: 0.3441)

Row 5, Col 6: Tile 4 (confidence: 0.5592)

Row 5, Col 7: Tile 8 (confidence: 1.0000)

Classification complete! Results saved to tile_classification.json

Grid size: 6 rows x 8 columns

Tile Array (2D):

Row 0: [8, 14, 5, 5, 4, 8, 8, 8]

Row 1: [5, 5, 5, 5, 14, 14, 15, 8]

Row 2: [3, 23, 8, 5, 5, 5, 5, 10]

Row 3: [10, 2, 5, 5, 5, 8, 5, 4]

Row 4: [8, 15, 14, 4, 8, 5, 5, 8]

Row 5: [8, 8, 8, 4, 5, 5, 4, 8]

Our test image - Actually was a 7x7 hexagonal grid. AND here’s a funny thing about hex-grids - An x-coordinate actually “shifts” in position depending on whether it is on an odd numbered row or an even numbered row (I’ll let you try to imagine this).

Definitely some progress to this. My gut is asking me to give up, but I need to try one more thing (I do have to

squeeze every token out of my pro plan!)

> Ok you returned a rectangular of 6 rows by 7 columns. However the image has 7 rows by 7 columns.

Second problem is in the image some sections won't have any tiles.

There I'd like your classifier to return a "0" - those represent "holes" in maps.

The third thing Id like you to do is to think about Hex tiles are laid out. They are not in a rectangular grid.

The "x" position of the first tile in odd-number rows are always half-tile-width greater than the even-numbered rows.

Think about how to represent this.

Ok so now we have the third type of classifier. The all-hailing Hex Map Classifier which hard coded the number of rows and columns to 7. D’oh. Ok another quick scolding gave us the even better dynamic version - Dynamic Hex Map Classifier:

> You are hardcoding the number of rows and columns. You should not be!

Ok certainly looks promising:

...

...

Row 5, Col 1: No good match (confidence: 1.0000)

Row 5, Col 2: No good match (confidence: 0.8929)

Row 5, Col 3: Tile 4 (confidence: 0.6809)

Row 5, Col 4: Tile 5 (confidence: 0.1701)

Row 5, Col 5: Tile 5 (confidence: 0.0789)

Row 5, Col 6: Tile 4 (confidence: 0.5907)

Row 5, Col 7: No good match (confidence: 1.0000)

Classification complete! Results saved to dynamic_hex_classification.json

Grid size: 6 rows x 9 columns

Dynamic Hexagonal Map Array (0s for holes):

Row 0: [0, 14, 5, 5, 7, 0, 0, 0, 0]

Row 1: [5, 5, 5, 5, 14, 14, 15, 0, 0]

Row 2: [4, 5, 5, 5, 0, 5, 14, 10, 0]

Row 3: [10, 23, 5, 0, 5, 5, 5, 14, 0]

Row 4: [0, 15, 14, 4, 8, 5, 5, 5, 4]

Row 5: [0, 0, 0, 4, 5, 5, 4, 0, 0]

Visual representation (0 = hole, numbers = tile types):

Row 0: 0 14 5 5 7 0 0 0 0

Row 1: 5 5 5 5 14 14 15 0 0

Row 2: 4 5 5 5 0 5 14 10 0

Row 3: 10 23 5 0 5 5 5 14 0

Row 4: 0 15 14 4 8 5 5 5 4

Row 5: 0 0 0 4 5 5 4 0 0

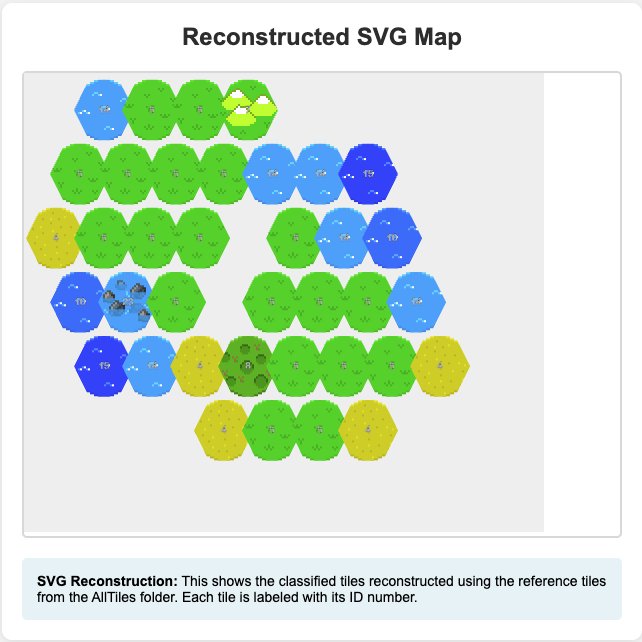

But this is going to get hard to debug. Let us whip up a visualizer too:

> Great. Ok let us create a visualizer (in python) tool that can represent the output of the classified tile array as an svg hex map using the

AllTiles/<tileNumber>.svg. The output should a html page with a .svg showing in it alongside the original image (map.png).

Result: Hex Map Visualizer

A picture is worth a 1000 words. Or rather is great for invalidating a 1000 classifier results! Sadly while our tile

table looked fancy, the visualizer showed a different picture.

Try Hashing ¶

At this point my patience was wearing thin but my OCD wasn’t letting me give up. Me explaining to the LLM in English was painful (sorry but English is not a better programming language). I wanted to try something more automatic.

In strings - especially large ones - performing bytewise comparisons are very slow so hashes can be used to test for equality. Or rather they can be used for quick check to see if two strings are NOT equal. If hashes are not equal, the underlying strings would NOT be equal. However if two string hashes are “equal” then (and only then) would we need to check for full byte-by-byte comparisons.

We can do something in images. However unlike text - we are interested in similarities rather than strict equality. Images can be altered slightly (flipping a single pixel) with very little perceived difference to the human eye. So what is needed is a fuzzy hash that can provide a fingerprint of an image that can be used to compare with another image. This works well with signals in general were values are NON-DISCRETE values. One such technique is the Perceptual Hash.

I wont go into the details of Perceptual Hashing (and the whole world of signal analysis - you should definitely check out Fourier Transforms and Wavelet Transforms).

As you can guess I wanted the LLM to use P-Hashing to test out the generated images (of the hex tiles) against the original map (The astute reader might me wondering why I did not ask the LLM for equality etc - well I’d say if you got it, then flaunt it!):

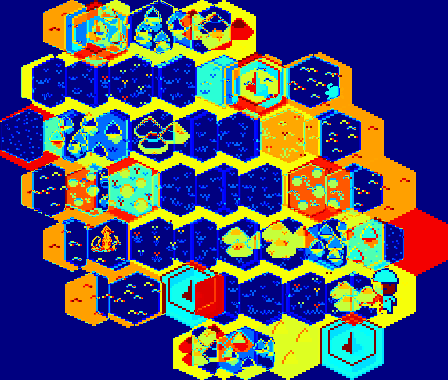

> Ok I need you compare what you are producing. Use a p-hash mechanism to measure what you produced with the original image.

Result: The Image Visualizer

Here was a resultant diff between expected and produced images:

This was great but our accuracy had not increased. I then realized that the tile rendering itself was broken.

> You have very low similarity. If you detected the right tiles AND generated the right shapes it would have been a lot more closer. Also the structure

is not current. You are generating hex in the wrong "angle". The tiles should be adjacent "left to right" with one side touching. And sides would touch

"diagonally".

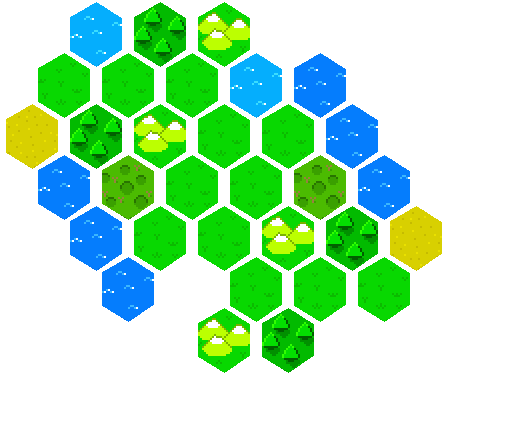

This seemed to click something off. It went on a frenzy generating an improved classifer and rendering. Finally we are seeing a decent generated image based on the new weights:

$ python correct_hex_classifier.py

...

...

Found tile at (5, 3): 5 (confidence: 0.2130)

Found tile at (5, 4): 5 (confidence: 0.2438)

Found tile at (5, 5): 5 (confidence: 0.5221)

Found tile at (6, 3): 7 (confidence: 0.3218)

Found tile at (6, 4): 9 (confidence: 0.2540)

Classification complete! Found 32 tiles

Grid size: 7 rows x 7 cols

Correct Hex Map Array:

Row 0: [0, 14, 9, 7, 0, 0, 0]

Row 1: [5, 5, 5, 14, 10, 0, 0]

Row 2: [4, 9, 7, 5, 5, 10, 0]

Row 3: [10, 8, 5, 5, 8, 10, 0]

Row 4: [0, 10, 5, 5, 7, 9, 4]

Row 5: [0, 10, 0, 5, 5, 5, 0]

Row 6: [0, 0, 0, 7, 9, 0, 0]

And to generate the image:

$ python correct_hex_generator.py

Showing us:

Voila! Well, sort of. While this version came close (a few of the tiles were wrong - eg the “base” on the top left being replaced by an “ocean”), let’s be honest about what actually happened here.

The Diminishing Returns of Vibe Coding ¶

What started as a simple “extract hex tiles from this image” request turned into:

- Multiple iterations of increasingly complex scripts

- Manual debugging of confidence scores and tile classifications

- Hand-holding the LLM through hexagonal grid geometry

- Constant course corrections when the approach went off track

- Hardcoded parameters for what should have been a generic solution

By the end, I was essentially dictating the solution step-by-step while Claude implemented it. The “AI magic” had devolved into me being a very expensive rubber duck debugger. This in itself is not a bad thing but not every solution needs a hammer.

The Real Problem: All-in-One Thinking ¶

The fundamental issue wasn’t with Claude’s capabilities - it was with my approach. Even though I’ve always been fervently against the “keep smashing that continue button” approach, I too had fallen into the classic “Vibe Coding” trap of assuming that throwing an entire complex problem at an LLM would yield a complete solution. “Just look at this image and extract all the tiles”, “Just look at the difference and course correct”, “Just take the feedback and course correct”, “Just … one more thing …” - how hard could it be?

Very hard, as it turns out. Not because the individual components are impossible, but because:

- Image processing requires domain expertise that’s hard to convey in natural language

- Computer vision problems need iterative debugging with visual feedback at each step

- Edge cases dominate - the difference between “kinda works” and “production ready” is enormous

- Composite problems need decomposition before AI can effectively assist

The all-in-one approach was fundamentally flawed. I was asking Claude to be simultaneously a computer vision expert, a hexagonal geometry specialist, and a tile classification system. When it struggled with one aspect, the entire solution became unreliable.

The Vibe Coding Trap ¶

This experience taught me quite a few lessons (and refreshed some old ones) about AI-assisted development: following every LLM suggestion is not the same as successful collaboration. I had become a passive participant in my own project, accepting each successive iteration without stepping back to question the fundamental approach.

The warning signs were everywhere:

- Solutions getting more complex instead of simpler

- Confidence scores being tuned instead of addressing root causes

- Hardcoded parameters replacing robust algorithms

- Each “fix” introducing new edge cases

I am more vindicated now that real collaboration with AI requires human leadership. You just have to know when to accept suggestions, when to pivot approaches, and when to break problems down into manageable pieces. And even better if you know what to build AND how to build it (use the AI as a fantastic Code Search and Tree Transforming engine).

The Path Forward ¶

As I was on this journey, it started to creep up on me that a completely different approach was needed. Ofcourse my ego

wouldnt let go. Instead of asking Claude to solve everything at once, I needed to:

- Decompose the problem into discrete, solvable components

- Lead the architecture decisions while letting AI handle implementation

- Build incrementally with validation at each step

- Apply domain knowledge to guide the solution

I think we as engineers know this but each one has to come to the realization at their own pace/time. I had to get to

a more “domain-specific” approach - SOmethign that was methodical, human-led and would leverages AI for what it does

best while maintaining human oversight for what we do best. This is what we will look at in Part 2. Not everything

needs an LLM all the time. There are some good old techniques that would come to my rescue.

Lesson: If you want one takeaway, it is - Games are Fun beyond just playing them!

Well if you need a second lesson more on the topic: AI usage is here whether you like it or not (which I love). So the most important skill is not going to be button smashing, but being able to break down a problem, use domain expertise, think architecturally - you know - Good old fashioned software engineering (Ah the sweet irony).